I recently moved to the charming village of Glen Ellen, CA.

I have found myself a kindred spirit (sans overwhelming global success and fortune) with the late great Glen Ellen Villager, Jack London. London, most famous for his novel The Call of The Wild.

He, along with myself traded a life of hustle and bustle in San Francisco for bucolic verisimilitude in Glen Ellen, CA.

Granted, I do have the benefit of gigabit fiber 😀

Imagine, my deep delight, discovering that another iconoclastic idol of mine, Hunter S. Thompson, not only lived in this charming little hamlet...he even memorialized it in writing!

I did some cursory searching and was unable to find a transcribed version of this essay...so...I learned how to use some basic OCR libraries and filled the gaps with good ol'fashioned typin'.

Below you will find Hunter S. Thompson's article in the August 1967 issue of Cavalier magazine titled...

Nights In The Rustic

Hunter S. Thompson writes about slow afternoons when patrons turn to the Rustic—a California saloon that still has charm... and Jack London tradition.

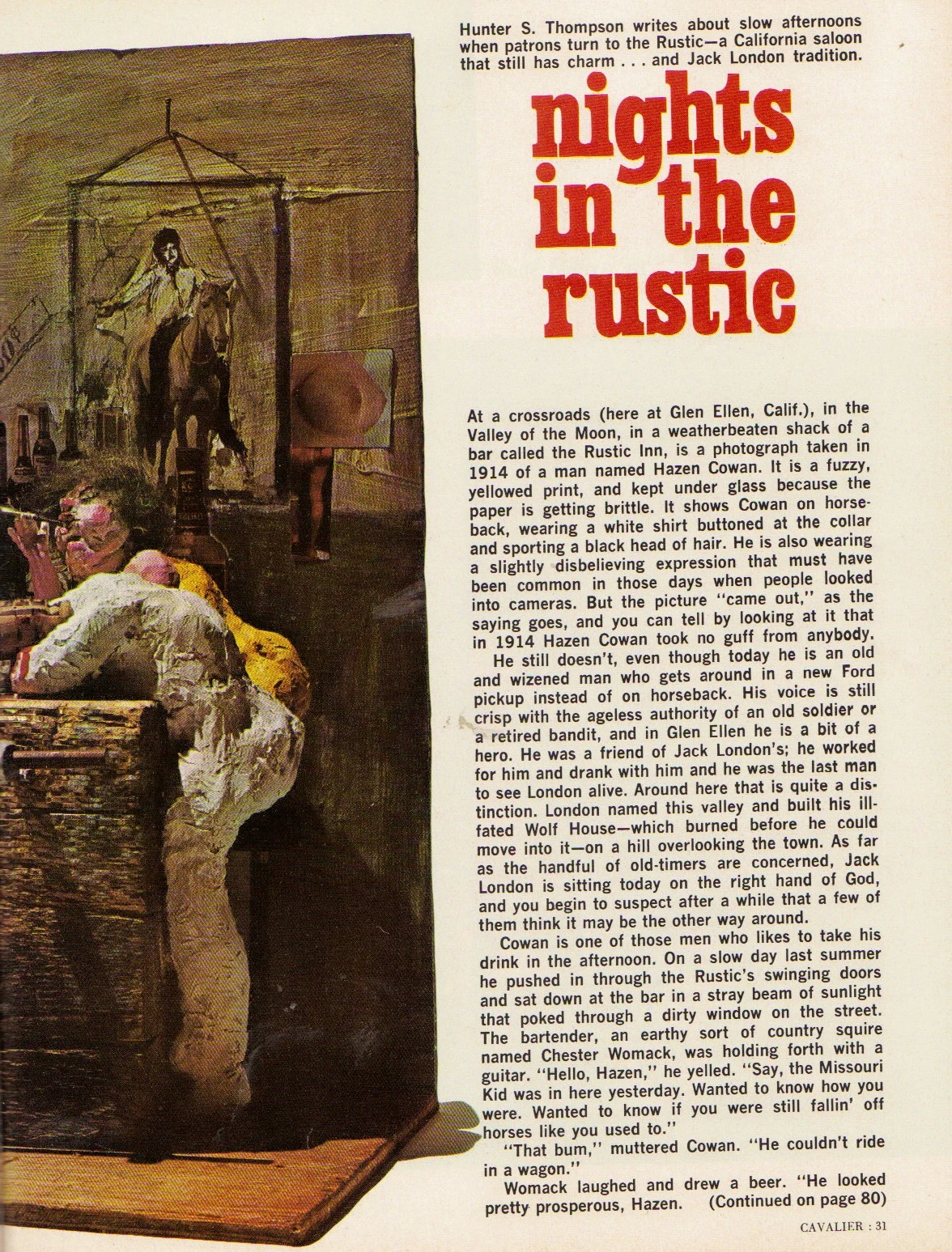

At a crossroads (here at Glen Ellen, Calif.), in the Valley of the Moon, in a weatherbeaten shack of a bar called the Rustic Inn, is a photograph taken in 1914 of a man named Hazen Cowan. It is a fuzzy, yellowed print, and kept under glass because the paper is getting brittle. It shows Cowan on horseback, wearing a white shirt buttoned at the collar and sporting a black head of hair. He is also wearing a slightly disbelieving expression that must have been common in those days when people looked into cameras. But the picture "came out," as the saying goes, and you can tell by looking at it that in 1914 Hazen Cowan took no guff from anybody.

He still doesn’t, even though today he is an old and wizened man who gets around in a new Ford pickup instead of on horseback. His voice is still crisp with the ageless authority of an old soldier or a retired bandit, and in Glen Ellen he is a bit of a hero. He was a friend of Jack London's; he worked for him and drank with him and he was the last man to see London alive. Around here that is quite a distinction. London named this valley and built his ill-fated Wolf House—which burned before he could move into it—on a hill overlooking the town. As far as the handful of old-timers are concerned, Jack London is sitting today on the right hand of God, and you begin to suspect after a while that a few of them think it may be the other way around.

Cowan is one of those men who likes to take his drink in the afternoon. On a slow day last summer he pushed in through the Rustic’s swinging doors and sat down at the bar in a stray beam of sunlight that poked through a dirty window on the street. The bartender, an earthy sort of country squire named Chester Womack, was holding forth with a guitar. "Hello, Hazen," he yelled. "Say, the Missouri Kid was in here yesterday. Wanted to know how you were. Wanted to know if you were still fallin’ off horses like you used to.”

“That bum," muttered Cowan. "He couldn't ride in a wagon.”

Womack laughed and drew a beer. “He looked pretty prosperous, Hazen. He's livin' over in Cotati these days-had a fine looking young woman with him, must have been his old lady."

"He's a deadbeat," said Cowan. “He’s owed me money for thirty years.”

Womack winked at somebody down the bar. He and a local lawyer named Jack Coffey are co-owners of the Rustic and they both enjoy the atmosphere. Womack is a self-styled soldier of fortune, semi-retired now, with a beautiful Mexican wife and a second home in Guadalajara. Unlike Coffey, Womack likes to tend bar now and then. It gives him a chance to wear his “Missouri overalls” and bait the old-timers like Cowan, who have long since come to terms with Chester’s machete sense of humor.

Not long after Cowan arrived that afternoon, a man and a woman came in. He had a camera around his neck and wore a straw hat that looked like it came off a sidewalk in Tiajuana; the woman wore a “golf” outfit and sunglasses. They sat down at one of the big redwood slabs that serve as tables in the Rustic, and waited nervously for a waiter to chronicle their needs. No one seemed to notice them.

Womack, who does not wait tables, picked up his guitar and began to sing: “O the hair on her belly was a strawberry color.”

The man bolted out of his chair and jerked his wife toward the door; obviously, this was worse than Tiajuana.

“Don’t go, folks,” yelled Womack. “I’m just singing a song about my old mare. Didn’t you ever hear about the Strawberry Roan?”

The swinging doors fanned air and Womack chuckled sadly. Then he proceeded to finish his lewd and brutal song. Cowan listened without comment. “Fat Pat,” a longtime regular, giggled in her English accent: “He’s too much, he’s just too much!” Don, the night bartender with a black patch on one eye, smiled more out of habit than amusement and leaned back against a montage of Jack London photos. Another day, another gone dollar, another dirty ditty at the Rustic Inn.

It is known as “Jack London’s favorite saloon,” but on the sign above the front door the word “saloon” is covered with a piece of sagging cardboard. The state Alcoholic Beverages Commission has decreed that there are no “saloons” in California. Nor are there any “bars,” “bookie joints” or “whorehouses.” All erstwhile saloons and/or bars have been replaced by “inns,” “clubs,” “cafes,” “lounges,” and a bottomless grab-bag of sly euphemisms advertising places where people can get publicly drunk. There are no “bars” even in San Francisco, which maintains one of the highest alcoholism rates in the nation.

The cardboard censor’s blot has not had much effect on the patrons of the Rustic Inn. It was not Jack London’s favorite saloon, but the disappearance of all the originals left an obvious vacuum, which the Rustic was quick to fill. It commands the approach to the Wolf House property—which is now Jack London State Park—and the connection is so blatant that it would take the most churlish kind of mind to deny the image of the wild-eyed writer thundering down the hill on his black stallion, shouting for booze.

The people who make the Rustic a popular saloon are inordinately receptive to the image. Many come from the cities, or from “the east”—which in California can be almost anywhere—and they come to drink and be entertained, not to split hairs about history. The Rustic serves one of the best fifty-cent drinks west of the Rockies. It also serves local color in large dollops. The heavy presence of Jack London makes some of the locals seem like rejects from Actors’ Equity and lets them get away with behavior that would be patently intolerable in bars without “character.” It takes a while to realize that they aren’t simply putting on a show. The action in the Rustic is a carbon copy of what frequently goes on in other bars around the Valley, but none of the other places have a Jack London tradition to charm the weary traveler and provide a frame of reference.

The strange truth is that the Rustic, unlike most “legendary” bars, has not become safe and respectable with fame. London’s people still frequent the place, abusing the tourists in all manner of ways, ranging from senseless violence to simple, delcarative statements like: "You're an ass buddy -- I'm takin' your wife home with me." This sort of thing creates tension and is said to make the Rustic an "interesting place to drink." Which is hard to deny, because on any summer weekend large numbers of tourists drive fifty miles out of San Francisco to stand around the saloon and be menaced. If they are living proof of anything beside the tedium of urban living, it is probably the fact that Americans are suckers for labels like “historic” or “traditional.” The dull truth is that they could drive five miles out of the city, or over to Oakland, and be abused in the same way at any cheap roadhouse—but not, of course, beneath portraits of Jack London, a fine set of elk horns and a whole gaggle of other relics ranging from old muzzle loaders to voodoo masks and diving helmets.

“The trouble with the Rustic,” says one ex-patron, “is that it’s too damned authentic. I get a kick out of reading about how wild and wooly it was out here in 1900, or watching it on a screen somewhere, but I get nervous when I have to drink with people who still act that way. The last time I was in the Rustic some drunken stevedore-type named Clem jerked me outside and said he’d beat my face in if I didn’t drive him right then to Petaluma, fifteen miles away, because he’d just run his truck into the river and had to get home. He showed me his truck; it was over the bank. On the way to Petaluma he said I could sleep with either one of his teenage daughters, but when we got there he jumped out of the car and kicked a big dent in the door. Who needs that kind of action? The next time I want to see how it was in the old days, I’ll watch Bonanza.”

But that is a romanticized view of the Rustic, which is really as contemporary as any neon-lit “Texas Bar & Grill” on any rural highway in the nation. The only difference is that the Rustic has an "Old West" facade, which seems to be one of the few gimmicks that will still lure urban dirnkers out there to mingle with their rural brethren.

Even so, there are random moments now and then when this place almost lives up to its image. I recall a winter night around Christmas, with maybe a half-dozen others at the bar, when I asked the bartender if he knew anybody in town besides Hazen Cowan who had known Jack London.

"Well, just that old guy sleepin' on the bar up there," he said, pointing to an old white-haried man passed out on the bar like a schoolboy taking a nap on his desk. "Hey, Wolf!" he shouted. "You knew London, didn't you?" He went up and shook the old fellow. “Wake up, Wolf. You been sleepin’ long enough.” Wolf felt like sleeping a bit longer, so we left him alone. “You see that picture there?” said the bartender, pointing to one on the wall. “That’s London giving a glass of wine to Martin Eden. You remember that name, don’t you? It’s one of his famous characters.” I recalled thinking that I hadn’t read any London since I was thirteen or so and barely remembered anything about him, much less about his characters. Just then the door opened and a woman came in—a person who might have been the original model for “The Face on the Barroom Floor.” Her entrance brought Wolf out of his stupor. “Hello there, Gertrude! Come’re and let me rub my nose in that fur collar.” He reached out like a man ready to catch a medicine ball. “Get away from my collar, you old goat!” Gertrude was in no mood to be dallied with. “Watch out now,” she snapped. “I'll have to scent this coat with mothballs if you come near it.” Wolf laughed distractedly. “Ha! At the stroke of midnight we'll fly to Reno! I’ll pay the freight!” With that, he fell back on the bar. Jack London looked down on us all, a young face, alert and half-smiling—supposedly his favorite photo, taken as he leaned against the rail of a ship, enroute to Alaska or Japan or some other place in the world that he traveled around as casually as some men drive today from Chicago to New York.

The World Book Encyclopedia takes a dim view of London; there one will read that he was a man “obsessed with brutal violence in almost every aspect.” Then it adds, with a wringing of editorial hands, that the world-wide image of Americans was more influenced by London than by any other figure until the advent of Hollywood. Bernard DeVoto, who edited a book of short stories, is more objective: “In 1918 Jack London was the best-known and highest-paid writer in the world. He made over a million dollars on fifty books and spent it all. He built himself a mansion, bought a ranch, sailed a yacht, and committed suicide because of debt, overwork, and liquor.”

London was nothing if not controversial, and it would take quite a while to sift the truth from all the swill that has been written about him. But it is not easy to see, by simply looking at his portrait, that he was “obsessed with brutal violence.” He looks, in fact, like a man of humor, even gentle; there is a wistful sensuality about him that suggests he might have been the original James Dean had he lived in the era of the press agent—which he did, in a way, but London’s agent was William Randolph Hearst, who made a roaring, wandering deity out of him, and created, in the process, the classic figure of the “foreign correspondent.” London was rich, famous, and a militant socialist by the time he was twenty-five. He died in 1916 at the age of forty, so long ago that he seems to belong to ancient history, and we can only wonder what he might have thought and said had he gone the whole route, like Douglas MacArthur, who was born only four years later than London, but who lived forty-eight years further into the future.

I was still pondering London when Wolf woke up again, seeming very agitated. “London?” he yelled. “Sure I knew London. Don’t bad-mouth that man! He had class! He used to come in here and buy drinks for the house all night. He was the only man in the valley who didn’t wear a hat but wore a wristwatch.” Wolf nodded emphatically, not toward any one of us, but in some vague direction of a dimly-remembered past now suddenly come to life—a brighter, better day when he could say what he meant without having to struggle in a deadly fog of booze and old age. “He was a goddamn gentleman! He'd listen to what you had to say because he liked people. Every now and then he’d go up to that feeble-minded home and listen to what them freaks had to say—that’s the way he was. Nobody bad-mouths Jack London while I’m around.”

“His name is Wolf Larsen,” said the bartender. “That’s what he says, anyway.” Wolf was watching us with un-focused curiosity. “I was born in Sweden,” he said...

“His name is Wolf Larsen,” said the bartender. “That's what he says, anyway.” Wolf was watching us with un-focused curiosity. “I was born in Sweden,” he said. “Been here since 1912. I’m the last man in the valley that went out on sailing ships, back and forth to Alaska—but now I’m retired and it’s the worst damn life in the world.”

A man who looked like a non- union plumber got up to leave, cursing Wolf as if it were part of the ritual of saying Goodnight; “You worthless old bum, can’t you ever be quiet? Go home, will you!”

Wolf laughed like he hadn't heard. “He’s only fifty. He don’t remember Jack London. I’m the only one left.”

“Hazen Cowan will outlive you by ten years,” said a voice in a pure Virginia Tidewater accent. It came through the smoky staleness of the place like some kind of odd music, an elegant sound in a room that was clearly unaccustomed to any sort of elegance.

Wolf parried it with a shout. “I’m an old-timer! I still call it Frisco! It’s only the old-timers can call it Frisco!”

“Then you must remember Cap- tain Billy,” said the Tidewater ac- cent. “You know, he used to put out the Whiz-Bang down in the city. He’s the one who first published "The Shooting of Dan McGrew and all those others. Remember that one? 'A bunch of the boys were whooping it up in the Malamute Saloon'... Hell fire, I use to know it word for word."

I leaned forward to see who was talking. He was a quiet-looking man in broad-brimmed felt hat, well in his cups, with white hair and a sort of maveric look about him, but not as old as Wolf or Hazen. "You remember "The Cruise of the Old Montana'?" he asked, looking around as if he really thought somebody might say, "Yeah, sure, I know it well." There was absolute silence in the bar as he started off: "'Now Billy was my kid brother with cheeks as smooth as a girl'....You remember that, sure you do."

But none of us did, not even old Wolf, who didn't even know his own real name and had to borrwo one from Jack London. Most of the others in the place were too drunk to remember where they lived. Against that background and in that sad climate the Tidewater accident was as welcome as the Old Crow that London liked for his thirst. The man had class, whoever he was, and for maybe twenty minutes on a slow weekday night the Rustic Inn was something special.

And so it goes, but not too often. On most nights the mood of the place is dull and schizophrenic. The 1890’s atmosphere is badly addled by 1960-style hoodlums looking for trouble, and the normal run of conversation is about on a par with any beerhouse in Anniston, Alabama. The elk horns seem unreal in the neon glow of the juke box, which features old standbys like “Sioux City Sue,” “Sorrow on the Rocks,” and “Skid Row Joe.” For a while there was an electric bowling machine, but Womack finally got rid of it. His touch is evident in some of the weird signs around the room and occasional newspaper clippings such as one on the Delano grape strike, which tells of a minister quoting Jack London on the subject of scabs—‘‘a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul”—and a fuzzy photo of a naked man tacked up beside a huge painting of a nude lady in a conch shell.

But there are not many people around who appreciate Chester’s humor, and pretty soon there won’t be anybody left who knew Jack London, It won’t make any real difference, because his name will still draw tourists, whether Hazen Cowan or Wolf Larsen are around, or not. For the moment, however, Cowan dresses up the place and the management makes every effort to have him in as often as possible. Unlike Wolf, he doesn’t particularly enjoy being on display. Cowan is authentic without being a menace to the tourist trade, which is far more than can be said of the general boozing bulk of Rustic’s clientele.

On most weekend nights the place fills up with one of the sleaziest mobs in all Christendom. Along with the regular handful of sad-eyed, pot-bellied frumps and the muscular women who work at the nearby hospital for the mentally retarded is a hard core of out-of-control customers who would tax the hospitality of the most venal innkeeper in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky.

The Rustic, in truth, is the sort of place where people grab you by the arm and say alarming things. The kind of drinking that goes on here would not be out of place in a Bolivian mining camp, 15,000 feet up in the Andes, where the Indian miners have a life expectancy of twenty-nine years.

It would not be out-of-place in Butte, Montana, either, or in most of the bars in east Los Angeles-but none of these places are rustic enough to attract the tourist trade. The same sort of brawl that would draw a dozen club-swinging cops to a bar in San Francisco's Mission District is dismissed with a friendly chuckle in Jack London's favorite saloon.

When I lived in Glen Ellen I stopped in the Rustic about every other day, but when I moved to the city I didn't go back for several months and after a while I began to wonder if things had changed. One Thursday night in late winter I returned, meaning to check it out. I arrived around midnight with a friend and found the place quiet. Four or five regulars were huddled at one end of the bar and some of the chairs were knocked over. The bartender's shirt was spattered with fresh blood and he seemed a bit tense. "We just had a beef," he explained. "Some old man came in with his son and a nephew just back from Vietnam. They sat there at the table and drank for an hour or so, then the old man started yelling, 'We can bust up anyone here - we'll bust you all!' Then it started. We had one of them down over there, then it went outside. They really wanted to hurt somebody. I guess it went on about twenty minutes. Jesus, there was blood all around."

By midnight the villains were gone and the scene had calmed down. Moe, the bartender, was helping his brother Paul take care of one of the locals who'd been whacked senseless in the fight. London smiled down on the scene as if he understood that it was all just a misunderstanding, as it were, among basically decent fellows who were bored, and had nothing better to do.

Transcription done via pytesseract and myself - there may be mistakes/omissions - let me know and I can fix